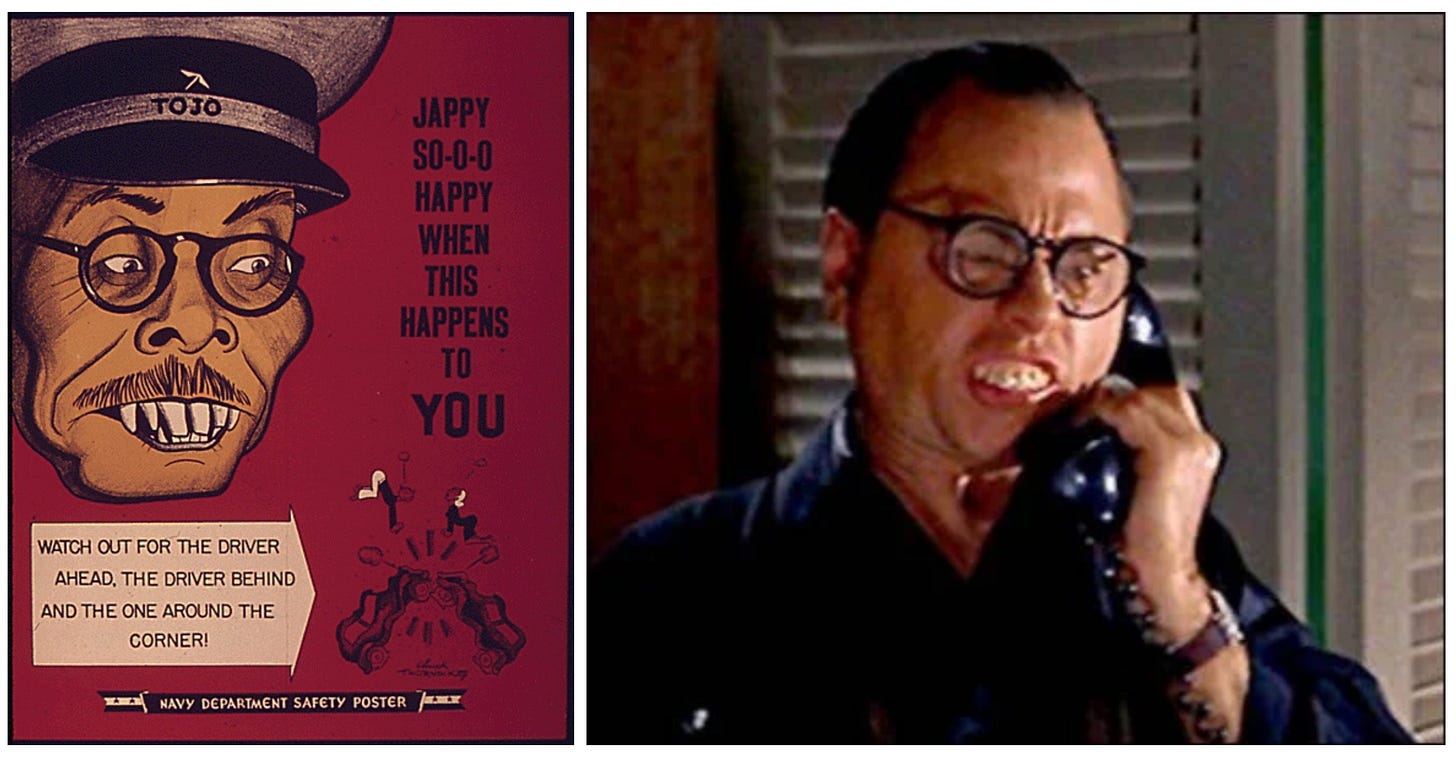

Last week, I examined the quintessentially American cowboy; this week, I’m drawn to the way that Asian Americans have historically been portrayed as more Asian than American. The perception of Asians as perpetual foreigners is deep-seated in American culture and media. The racist propaganda posters of World War II relied on the same powerful stereotypes drawn in 19th-century cartoons (and sometimes even earlier); the legacy of those posters is clearly visible in Mickey Rooney’s infamous portrayal of Mr. Yunioshi in the 1961 film Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

I’ve always wanted to watch Breakfast at Tiffany’s; the one time I tried, I was so disgusted by Rooney’s grotesque portrayal and the sheer hate it betrayed that I gave up on the movie before I was halfway through. I’ll revisit it eventually — I love Audrey Hepburn — but as I watched Rooney, I felt a gutpunch: How people must have hated us to not only allow this travesty but to find it amusing. (Sample review from the Chicago Tribune: “Mickey Rooney adds to the fun as a toothy Japanese.”) I knew this factually; I have done too much research on World War II not to realize the pure vitriol that some Americans felt towards Japanese people, whether they were American or not — but this portrayal felt like evidence in living Technicolor, all the worse because it was supposed to be funny.

My next thought was: what’s with American media and Japanese people with cameras?

Let’s start with Mr. Yunioshi. As I said, I’ve never seen the film all the way through, and I haven’t yet read the book, so I’m not exactly an expert; however, this Rafu Shimpo interview with the actor portraying Mr. Yunioshi in the 2013 Broadway adaptation of Breakfast at Tiffany’s is enlightening. The actor, James Yaegashi, explains that unlike Rooney’s ludicrously foreign characterization, the Mr. Yunioshi of Capote’s original novel was actually a Nisei from California. Where Rooney’s Yunioshi is creepily obsessed with photographing Audrey Hepburn’s Holly Golightly, with overtones reminiscent of the most lurid of propaganda, Yaegashi’s book-based characterization of Yunioshi is that of a man whose desire to photograph Holly is driven by artistic admiration for her beauty. In other words, there’s a great deal more complexity in the Mr. Yunioshi of Capote’s book — and nuance doesn’t exactly lend itself to slapstick humor. Despite the great lengths that, say, the 442nd went to prove otherwise 20 years prior, the film’s director Blake Edwards clearly felt that it was no big deal to portray the originally American character of Mr. Yunioshi as cartoonishly (and even sinisterly) Japanese. (Obligatory addendum: For what it’s worth, Edwards and Rooney later expressed regret over the character.)

+

But when did the stereotype of the camera-toting Japanese first appear? I can’t find a conclusive answer; the earliest instance of the stereotype I could find was in The Three Stooges’ Nazi-lampooning short “I’ll Never Heil Again,” aired in 1941. When a parody meeting of the Axis powers predictably ends with a brawl, the Tojo analogue pauses the melee a couple of times to snap a photo with a Japanese accent. (“Picture-uh.” Snap. “Sank you.”) But the very presence of the trope indicates that it was already well-established by 1941; it had to be, in order for audiences to get the joke. (And Stooges jokes are nothing if not obvious.)

The stereotype persisted in Rosemary’s Baby, novel (1967) and film adaptation (1968) alike. The “grinning and nodding” Japanese character, as he’s described in the book, is barely in either version, but he has a camera with him the whole time; his name (Hayato) is a throwaway line in the book, and he’s otherwise referred to as “the Japanese” or “a Japanese,” from Rosemary’s perspective. He even gets to close the book with a real kicker of a closing line: “The Japanese slipped forward with his camera, crouched, and took two three four photos in quick succession.”

In researching this essay, I found this absolutely fascinating interview with the actor who portrayed Hayato, Ernest Harada, from an occult-obsessed blogger. Like my own family members, Harada was born and raised in Hawaii. (He even shares an alma mater with my cousins — go Mid-Pac!) This man studied acting at the London Academy of Music and Drama Art, and his big break was playing “the Japanese” in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby. The way Harada talks about his childhood and his experience is insightful and eerily similar to my own grandmother’s recollections; I can’t recommend reading the entire interview strongly enough. (Harada also talks about being in Valley of the Dolls and being friends with Ruth Gordon — incredible.) But most relevant for this essay is Harada’s explanation for his character’s presence in the film:

I asked Roman about that. He said: “If you look around you see these Japanese businessmen all over the place and they all have cameras. They’re in groups of three and four and five, and they’re running all over the world—Europe, America—and they all have cameras. I wanted to put that in, so you’re it!”

So is the character of Hayato a tourist or a fellow resident of the Bramford building? We don’t know, and that’s because it doesn’t matter for Polanski’s storytelling purposes. He’s a Japanese with a camera; like the other characters in the film (overbearing neighbors, crotchety old lady), he’s unsettlingly familiar. His presence amplifies the sense of conspiracy by implying that this cabal has a global reach. From a film perspective, it’s deeply effective.

Despite being a third-generation (or sansei) Japanese American, Harada was also keenly aware of how he was perceived as inherently foreign. For Rosemary’s Baby, he put on a Japanese accent, which he notes wasn’t exactly a stretch because he’d heard it so often. However, Harada notes, when he would go to auditions and do a Japanese accent as requested,

…this one producer said, “That’s not a Japanese accent.” Excuse me? I asked him what he thought a Japanese accent was. And he said, “Like Richard Loo in all the World War II films.” I said, “Well I hate to inform you, but I know Richard Loo, he’s from Maui, and his accent is basically a Chinese accent. His name is Loo, that’s Chinese.” But then that was typical of the stereotypical treatment we got that I personally fought so hard against. Why can’t I speak the way I speak? I mean, you want the Queen’s English? I’ll give you that (mockingly as a perturbed producer): “Oh no! No!”

Harada’s experience is emblematic of a problem that Asian American actors still face today; they’re expected to portray popular misperceptions rather than reality.

+

Even in present-day depictions of the past, the stereotype resonates. In a Mad Men episode set in 1968 (“The Quality of Mercy,”) the characters react to seeing Rosemary’s Baby in theaters. “That was really, really scary,” shudders Megan. “It was disturbing,” concedes Don. Leaving the theater, they bump into SC&P colleagues Ted and Peggy:

TED: Peggy and I had an argument about whether there was a Japanese in the end. You know, when Mia Farrow walks in…

MEGAN: There was.

PEGGY: I know.

DON: So you’ve both already seen it?

TED: Yeah. But obviously, she remembered it better. She wants a Japanese in the ad.

MEGAN (laughing): They always have a camera.

They always have a camera. This seems to be a realistic portrayal of 1968: the stereotype is universally well-known, a trope that everyone can agree on. But why?

I still don’t know. This is a mystery that unexpectedly will take much more time to unravel than I have to write this newsletter; perhaps we can put it down to Japanese visitors having easier, cheaper access to portable cameras than their American counterparts; perhaps it’s a stereotype that originated in Europe and crossed the Atlantic. Maybe the fact that it’s often one guy with a camera has something to do with the initially disproportionally male Asian population in the US. The idea of Japanese tourists always having a camera is not necessarily racist in itself (heck, even Rick Steves wrote about it, bless him); it’s more baffling that it became accepted as a universal truth, in the same vein of French people wearing berets and Breton shirts. (But there’s a lot more discussion of that trope out there than that of the Japanese photographer / tourist.)

+

More than the camera, which is a puzzling but ultimately pretty harmless stereotype, the real problem with these portrayals is that they are inherently foreign. And that trope is much more deeply rooted. Being foreign is tied up with being mysterious and inscrutable: Asians are unknowable because they are foreign, and foreign because they are unknowable. Even Clarence Darrow, a man renowned for his intelligence and perspicacity, said as much when confronted with the then-rare challenge of a multiracial (including Asian) jury during a case he took in Hawaii: “There were Chinamen in the jury box, and Japanese, and Hawaiian and mixed bloods; it was not easy to guess what they were thinking about, if anything at all.” Yeah. (This case, by the way, was the infamous Massie trial, where Darrow came out of retirement to defend a Navy officer who essentially lynched a local Native Hawaiian boy. It is as insane as it sounds, and I’ll be revisiting it in future.) My point is that the photographer trope resonates with the perpetual foreigner trope; while all of these movie characters could very well be amateur photographers, they’re often really being depicted as tourists, and therefore Not From Here.

In his 2017 film Get Out, director Jordan Peele doesn’t even need the camera to powerfully deploy the perpetual foreigner stereotype. An accented Japanese man (named in the credits as Hiroki Tanaka, but uncredited in the movie), approaches Chris, the film’s Black protagonist, and asks with apparent sincerity, “Is the African-American experience an advantage or a disadvantage?” Though Chris has just been peppered with a dozen similarly racist questions and comments, it’s still a jarring moment. Later, (spoiler!!), we see the Japanese character place a bid on Chris in an auction to purchase his body. He’s the only non-white person participating.

As Jordan Peele explained it on Bobby Lee’s podcast Tiger Belly (noting that “people are writing essays about it” — guilty):

It’s a shoutout to Rosemary’s Baby, where at the end, there’s a Japanese guy there, and it paints the picture that this society is f–king far-reaching… and that’s scary. Two, because of the broken English, he’s gotta ask the question more directly, and it heightens the awkwardness of the situation. Lastly, yeah, what doesn’t make sense? Old Japanese billionaire guy comes…

As in Rosemary’s Baby, the use of the trope is powerful. And it’s something I still grapple with to this day. It’s Peele’s (incredible) film, based on his knowledge of the world and the way America is; his use of the trope is intentional, informed, and impactful. Yet it still draws on, and even reinforces, a decades-old racial stereotype in a movie about race. (Peele’s reference to Japanese billionaires also feels weirdly dated in a world where China has long overtaken Japan as America’s economic competitor.) I still debate with myself whether I feel the utility of the character outweighs its resonance with racist stereotypes. The actual question posed by the character feels like a provocative break through the fourth wall — would an aging Japanese man really be better off as a young Black man in America? — but again, the service it renders to Peele’s story is arguably detrimental to Asian representation in American film. (You can read a few Asian American reviewers’ reactions in this Rafu Shimpo article.)

+

In The Handmaid’s Tale, even a future version of America is not free of camera-wielding Japanese tourists. Margaret Atwood’s 1985 Tale depicts a dystopian America, called Gilead, where women are reduced to their biological and societal functions. As with Get Out, I found her usage of the trope particularly jarring because until that moment, I saw myself in the protagonist and the oppression she faces; as with Get Out, I was jolted out of that identification with a pointed reminder of precisely how I am unlike the protagonist — and even unwelcome. The narrator Offred, affected by the oppressive misogynistic regime she lives under, describes the tourists in their “normal,” revealing clothes in highly sexualized terms. She then says:

We are fascinated, but also repelled. They seem undressed. It has taken so little time to change our minds, about things like this. Then I think: I used to dress like that. That was freedom. Westernized, they used to call it.

The Japanese tourists come towards us, twittering, and we turn our heads away too late: our faces have been seen.

There’s an interpreter…the tourists bunch behind him; one of them raises a camera. “Excuse me,” he says to both of us, politely enough. “They’re asking if they can take your picture.”

I look down at the sidewalk, shake my head for No. What they must see is the white wings only, a scrap of face, my chin and part of my mouth. Not the eyes. I know better than to look the interpreter in the face…

The interpreter turns back to the group, chatters at them in staccato. I know what he’ll be saying, I know the line. He’ll be telling them that the women here have different customs, that to stare at them through the lens of a camera is, for them, an experience of violation…

“He asks, are you happy,” says the interpreter. I can imagine it, their curiosity: Are they happy? How can they be happy? I can feel their bright black eyes on us, the way they lean a little forward to catch our answers, the women especially, but the men too: we are secret, forbidden, we excite them.

Whether knowingly or not, Atwood has flipped the script on the way geisha, for example, are fawned over and objectified by foreign tourists. (In March, Kyoto officials closed parts of the historic Gion Kobu district to tourists in an effort to protect resident geiko and maiko from “out of control” tourist photos and harassment.) Offred feels violated by the Japanese tourists’ gawking; her customs are mysterious and inscrutable to these visitors with their “staccato” chatter. She is demure under the gaze of their “bright black eyes.” “We are secret, forbidden, we excite them,” she says. This could easily describe the same exoticizing white gaze that permeates countless Western works set in Eastern locales.

Atwood also uses the foreignness of the Japanese tourists (who are actually from Japan in this instance — no word on if there are any Japanese Americans in Gilead) to underline just how backwards this dystopian version of America is. The subtext: West has become East, which is to say, backwards. Unthinkable! This is a particularly subtle instance of white feminism at work. As with Get Out, the usage of the trope is effective in getting its point across; but the truths that it’s based on are questionable.

For me, this is a fascinating topic to research; it’s also personal. I have been asked as recently as this month if “the tiger mom thing is true” by someone after I said I’m Japanese; I’ve also been asked more often than I can count why I can’t speak Japanese, even though my family has been here for five generations. (I doubt the same person would ask an Italian American why they can’t speak Italian.) While we seem to have pretty much moved on from the camera stereotype, especially with the advent of smartphones, the perpetual foreigner trope lives on, and it’s hard to shake. As Asian representation in American media continues to grow, I’m ultimately hopeful; but stereotypes exert their own gravitational pull, and it will take us a long time to build a canon powerful enough to make our Americanness unquestionable.

Another great thought-provoking piece! I live in Hawaii, which I think is an outlier. Being part of the U.S. is a sensitive issue, we have large numbers of Japanese tourists, and Japanese have lived here since well before statehood. Yet, I see the issues on the mainland for sure!!

Thoughtful and interesting. So interesting to think about when and how the archteype emerged.