I wrote this essay for the first volume of my cultural journal Kioku a year ago. I’ve long wanted to publish it in another outlet; I figured, why not here? I hope you enjoy.

History isn’t written by the victors, but by the recordkeepers. As humans, we long not only to be remembered after death, but to be known and understood. In such cases, as the saying goes, the faintest ink is better than the sharpest memory. A well-kept diary or a meticulous biography can give the subject life for centuries after death.

This is why I love Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall trilogy, a masterpiece of historical fiction. Her Thomas Cromwell, reconstructed from his own and his contemporaries’ writings, looms as solidly in my mind as if I knew him personally. Her written portrait of him easily resurrected a man dead nearly 500 years. But this vivid work of art made it disturbingly clear how little I know about my own ancestors, and how distant and ghostly they are to me in comparison.

I come from a family of avid readers and writers. My mother is a professional communicator, and my grandmother is an English teacher. Even my grandmother’s father, a nisei trickster who once had to fish a library book out of a latrine, studied Shakespeare intently in his old age in the hopes of impressing his intellectual daughter.

Like all writers, we are dramatic. And like all readers, we fill in narrative gaps with our own imagination. As a result, I have only recently discovered that the rich tapestry of my family history owes much to my family’s embroidery. I don’t mean to say that the stories I grew up with were deceptive or even necessarily exaggerated, but that the threads of fact and firsthand knowledge have worn thin with time and distance, and that the older generations have attempted to patch and adorn them where possible.

The prime example is my great-great-grandmother Kise Yoshioka Nagai. Until recently, my image of Kise was entirely composed of family stories. To hear my mother (and my aunts, and my grandmother) tell it, Kise was a picture bride who sailed to Honolulu in 1908. After waiting for her husband Keitaro at Honolulu Harbor for a week, Kise was disappointed by his plain face and short stature. She was further dismayed by the red dirt and humble houses of the Helemano Plantation where they made their home. In one beautifully written short story, my aunt Megan imagined Kise’s temporary joy upon unboxing the elegant, Western-style hat that she wore in a portrait we have of her.

Kise’s loveliness was foremost in our family storytelling. “The others called her ‘the Waialua Beauty,’” my grandmother wrote, “and indeed, Kise was beautiful, with her melancholy liquid brown eyes and tall slender nose and elegantly shaped figure.” She goes on to remark that it was no wonder the other plantation wives (presumed to be common-looking) were jealous of her aloof, willowy beauty.

Our own recordkeeping reveals the weight my family placed on physical beauty, and our own vanity in underlining the loveliness of our ancestors. If the first thing I learned of Kise was her brave journey as a picture bride, the second was her supposedly remarkable beauty. However, my family never equated beauty with goodness, or even necessarily good fortune. It was always clear to me that Kise’s unusual beauty did nothing to shield her from some of the most base and common hardships of her time.

My grandmother’s meticulous family history goes on to detail Kise’s indisputably difficult life: She raised two daughters on her own after losing her infant son to umbilical strangulation and her gentle husband to the 1918 flu pandemic. (He fell ill after diligently nursing a sick neighbor.) With no other choice, Kise worked as a seamstress to make ends meet. She never married again, and she never learned to speak English. As she aged, she grew increasingly bitter and isolated as she attempted to beat her spirited American daughters into submission. My grandmother remembers her as a sullen figure subsisting on Bull Durham tobacco. After a long and difficult life, she died, to my great-grandmother’s everlasting horror, after falling on her face and breaking her tall nose. My family may have romanticized my idea of Kise, but I don’t think they can be accused of glamorizing it.

One day, my grandmother, the family historian, discovered a record that established that Kise had married Keitaro in Japan a year before emigrating – contradicting the long-held picture bride narrative. Unsentimental family members mocked the discovery, as if we had always portrayed Kise as a tragic, trafficked woman and our identities must now somehow readjust to this new reality. “So much for the human trafficking!” they scoffed, as if we had behaved like martyrs. In truth, it changed nothing essential of the story I knew; Kise was a woman, and she had suffered, and her suffering had allowed us to exist.

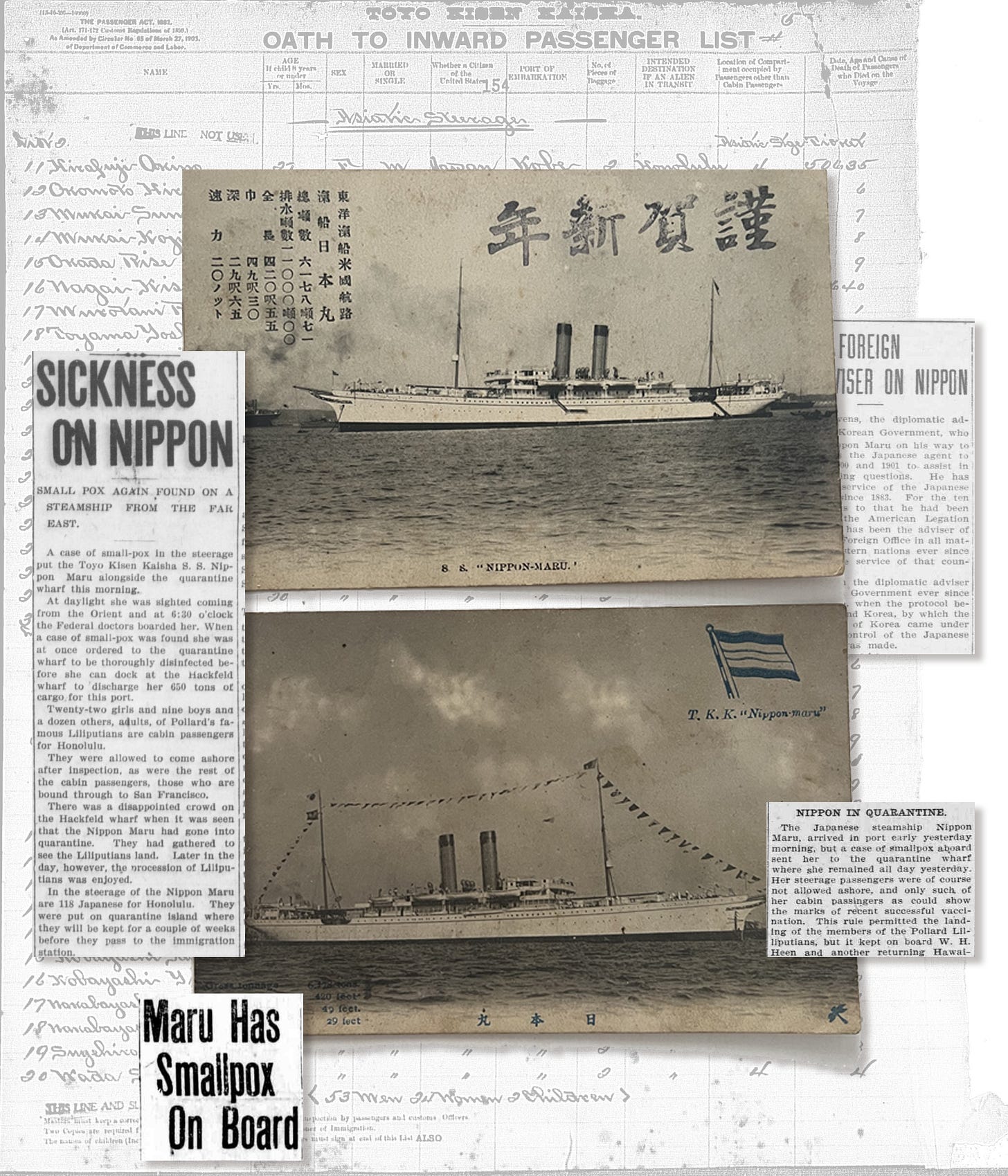

I was nettled by this scorn and decided to go on my own journey to find Kise. Incredibly, endless pages of ship manifests have been preserved and are now searchable online. Through hours of research and deduction, I tracked down the original ship that Kise arrived on: the Nippon Maru, a massive ship from the Toyo Kisen Kaisha (T.K.K) line. I narrowed down her arrival date to March 13, 1908.

Armed with these powerful search parameters, I sifted through dozens of issues of English-language Hawaiian newspapers. Hawai‘i had a robust and diverse newspaper industry for a small kingdom (or territory, as it was by then). There were various English-language dailies, Hawaiian-language newspapers, and multiple Japanese-language newspapers with differing (and even, at times, opposing) editorial perspectives. Though I am linguistically limited to the English-language papers, they are so full of random and wonderful detail that they paint a vivid, textured image of the world around Kise. It is Kise that remains elusive and flat, a mysterious void for me to project onto.

If nothing else, the newspapers revealed that our family could not be accused of exaggerating Kise’s difficult voyage. Her journey was actually arduous enough to be newsworthy. The Nippon Maru’s captain, the dashing William Woodus Greene, said the voyage was

the roughest trip he has ever experienced in the steamer. Great giant waves, which warped themselves over the Bows of the trim liner and spread themselves far above the smokestacks, continually assailed the vessel. Often and often the Nippon Maru had to be slowed down to minister to the comfort of the passengers. At Kobe a snowstorm was raging, and the vessel was white from stem to stern with falling flakes.

As a Japanese passenger, Kise was restricted to Asiatic steerage—the Asian section of third class, where passengers bunked in close proximity in dormitory style cabins. One can only imagine the effect of those “great giant waves” on the passengers crammed below deck.

Then things got even worse: smallpox broke out in steerage. The Pacific Commercial Advertiser noted, “...steerage passengers were of course not allowed on shore, and only [those] cabin passengers as could show the marks of recent successful vaccination.” The Hawaiian Star alerted the public to smallpox “again found on a steamship from the Far East,” and noted in passing the “118 Japanese for Honolulu” that would be forced to quarantine “for a couple of weeks” before going to immigration. This explains Keitaro’s heretofore mysterious delay in meeting Kise at the harbor. I was intrigued to discover that Kise was held at the descriptively named “Quarantine Island,” later called “Sand Island,” which was still later an incarceration center for members of Hawai‘i’s Japanese community during World War II.

In addition to the smallpox, Kise’s arrival was particularly well-documented because of the celebrities that sailed with her. The Nippon Maru was carrying a popular children’s troupe: “Pollard’s Lilliputians.”

...Pollard’s famous Lilliputians are cabin passengers for Honolulu. They were allowed to come ashore after inspection... There was a disappointed crowd on the Hackfeld wharf when it was seen that the Nippon Maru had gone into quarantine. They had gathered to see the Lilliputians land. Later in the day, however, the procession of Lilliputians was enjoyed.

The petite performers were not as beloved by their fellow first-class passengers, who “spoke bitterly of the discrimination shown by Dr. St. Clair of the quarantine service.”

When the Japanese liner reached Honolulu, according to those on board, the health authorities at Honolulu allowed a whole theatrical company to land, but refused to let the other saloon passengers leave the steamer. The cabin passengers yesterday were almost unanimous in their complaints against the partiality shown, though Captain Greene, when seen, expressed the opinion that the Honolulu officers had acted reasonably in the matter.

The fortunate Lilliputians repaired “directly to the Royal Hawaiian Hotel, to rest up for the big performance.” (Their multiple-show run was later effusively praised across island publications.)

As for the smallpox, the newspapers had a field day with the unfortunate Chinese man who had fallen ill on the ship. His name was alternately reported as “Sup Sam” and “Wong Yook Ming.” Speaking as a non-expert, the latter name sounds more likely; in either case, he was deemed ill-fated. (Among the supposed rationales: Sup Sam means thirteen; Wong means yellow, the color of a quarantine flag; he was passenger number thirteen on the manifest; and either fell ill or arrived in port on Friday the 13th, depending on the newspaper.)

Also unlucky were the passengers who had already endured a long and grueling journey only to wait for an unknown length of time in quarantine, under conditions which can only be imagined. Another illustrious member of the ship, lawyer W.H. Heen, was forced to go to Quarantine Island as well, though he stayed “as the guest of Dr. James,” which presumably afforded more comfort than wherever the steerage passengers were quartered. Heen would later be the defense attorney for Joseph Kahahawai, who in 1932 was kidnapped and murdered in a case that both eerily resembled that of Emmett Till 23 years later and laid bare the racial and cultural dynamics unique to Hawai‘i.

There were still other high-profile passengers on the ship, including D.W. Stevens, a diplomat at the center of much international intrigue. These passengers’ releases from quarantine after several days were newsworthy; as far as I know, the steerage passengers’ were not, and the length of Kise’s stay on Quarantine Island is still a mystery.

The newspapers paint a vivid picture of the conflicted world Kise sailed into; ads for prosperous Japanese-owned businesses bump up against ads touting goods made with “white labor.” Endearingly local stories are covered on the same sheet as consequential world events. The Prohibition movement simmers throughout the sheets, building to a rolling boil.

All of these intersecting threads of history are alluring in their own right. Kise’s arrival in Honolulu is connected to so many other fascinating parts of Hawaiian and Japanese American history. But though Kise may have walked alongside prominent personalities, they would have overlooked her as another of the “118 Japanese” in steerage on the Nippon Maru, or one of the tens of thousands that were populating the islands. Even if I could look for her name in the Japanese-language newspapers, I am not sure if I would find it. The gap between recordkeeping for the “notables” and for an ordinary immigrant like Kise is striking, and so vast that I am not sure if I can bridge it.

The few records I have of Kise’s life are precious: the bango (number) that her husband used to charge goods at the plantation store and his carefully inscribed English signature on his World War I draft card. I have the manifests and census statements and even Nippon Maru postcards I purchased on eBay that give me the outlines of Kise’s journey. Thanks to manifests, I know that when Kise arrived, she was 20 years old, 5’1.5”, with a scar on her left forefinger. But she remains as ghostly and unreal as ever.

The information that I have about Kise as an individual is both scant and complicated. Her daughters have both long since passed, wracked by guilt for their inability to fully care for their angry and impoverished mother. My grandmother only knows what her mother told her, and while these emotional daubs of color paint a vivid picture, they are not the full story. My grandmother’s mother undoubtedly kept much from her children. Characteristically for her generation, she did not like to linger on painful truths. Far from the type of detailed oral history that is necessary to preserve a person in the absence of formal record-keeping, Kise’s children were sparing in their words. I cannot blame them, but I mourn our tenuous connection to our family’s long history in Japan.

In my journey, I do not seek romance or tragedy; I want to know Kise, and to hope that in doing so, I can give her the peace of being known and recognized as she deserved to be in life. I do not imagine a saint; I see a woman, and a mother, however flawed. I perceive a person who must have had her own aspirations and personal desires, and dreams that presumably were not fixated on the vague idea of paving the way for future generations. I search for her, not least because understanding Kise will allow me to better understand her daughters and the burdens they in turn passed to their daughters and nieces, and them on to me.

When I think of Kise as a widow, bitter and angry and abusive, I imagine her anguish and frustration in her inability to make herself understood. However she felt inside, whatever she wanted to say, it does not seem fair to me that she should remain eternally mute.

In short, I look for Kise because she is more than my family’s foothold in America. There is a certain degree of guilt in the act of searching: it feels like a form of penance, an act of filial piety akin to the careful cleansing of gravestones that I know is a ritual for dutiful Japanese mourners. In some ways, it feels like the least I can do is to uncover the hard life that paid for my comfortable existence.

Kise rests now in a canister-shaped copper urn in the Wahiawa Hongwanji Mission Temple, in a glass-fronted niche in a quiet pleasant room. She is with her husband and surrounded by her daughters and my other ancestors. Though I can view her ashes and bring her flowers, Kise in her Wahiawa Hongwanji niche feels more unknowable to me than Thomas Cromwell in his chilly grave under the Chapel Royal of St Peter ad Vincula.

But it is the hope of knowing her that pulls me ever onward through reams of dusty pages, scribbled censuses, and stamped tickets. I struggle to transform paper and ink into flesh and blood. I may never have enough to bring Kise to life. But as I pore over the documents, I pour water over her gravestone, and gently scrub the dirt away, hoping that the act will bring her before me one day.

This is beautiful. Such a wonderful telling of the effort to catch wisps and ashes of an ancestor’s life. For those for whom it’s not too late, Let’s Talk Story is a book designed to bridge the generation gap and capture those stories!

https://letstalkstoryclub.org/purchase-a-book/ (Shiono)

All proceeds benefit the Go For Broke National Education Center ❤️